Michigan iconographer roots work in prayer when depicting the divine

Kathleen Bordo Crombie stands next to an icon of St. Francis of Assisi, dedicated to her late husband, Robyn. The Church of the Divine Child in Dearborn, Michigan, parishioner took up iconography after taking a class at the Sacred Art Institute of St. Edmund’s Retreat Center on Enders Island in Mystic, Connecticut, where she learned iconography is rooted in depicting the image of God. / Credit: Daniel Meloy/Detroit Catholic

Kathleen Bordo Crombie stands next to an icon of St. Francis of Assisi, dedicated to her late husband, Robyn. The Church of the Divine Child in Dearborn, Michigan, parishioner took up iconography after taking a class at the Sacred Art Institute of St. Edmund’s Retreat Center on Enders Island in Mystic, Connecticut, where she learned iconography is rooted in depicting the image of God. / Credit: Daniel Meloy/Detroit Catholic Detroit, Mich., Jun 30, 2024 / 06:00 am (CNA).

Praying before an icon is like having a meeting with your favorite saint, according to Michigan-based iconographer Kathleen Bordo Crombie.

When a person gazes upon the holy artwork, it’s not as if he or she is looking at an artist’s interpretation of a saint; rather, he or she is getting a glimpse of how God sees that person. And because every person is made in the image of God, praying with an icon is an interaction with the divine, something Crombie doesn’t take lightly in her work as a Catholic iconographer.

“‘Icon’ is Greek for ‘image.’ Every holy divine person that goes on a board for an icon is the image of Christ, as we are all created in the image of Christ,” Crombie, a member of Divine Child Parish in Dearborn, Michigan, told Detroit Catholic. “There is a theology in the preparation of the board, like how the old monks would take an old altar cloth and put it over the board and glue it down and the image would go over the top. They were preparing the board to receive the image of Christ, like preparing the altar for the Eucharist.”

Crombie has been an iconographer since the early 2000s after attending a workshop at the Sacred Art Institute of St. Edmund’s Retreat Center on Enders Island in Mystic, Connecticut.

Crombie displays samples of her work in her home office, including one of Blessed Carlo Acutis, with Carlo depicted as wearing sunglasses and the Wi-Fi symbol to the left of the icon.

She previously had a career in contemporary basket making before working for Right to Life of Michigan for 18 years as director of gift planning, but she felt God’s calling to get back into art, only this time art for his sake.

A friend suggested taking a class at the Sacred Art Institute, but the only class that fit her schedule was iconography, something she knew nothing about.

“I remember thinking, ‘Do I like icons?’” Crombie recalled. “I know they are kind of weird-looking. I know they are holy, but I didn’t know a lot about them.”

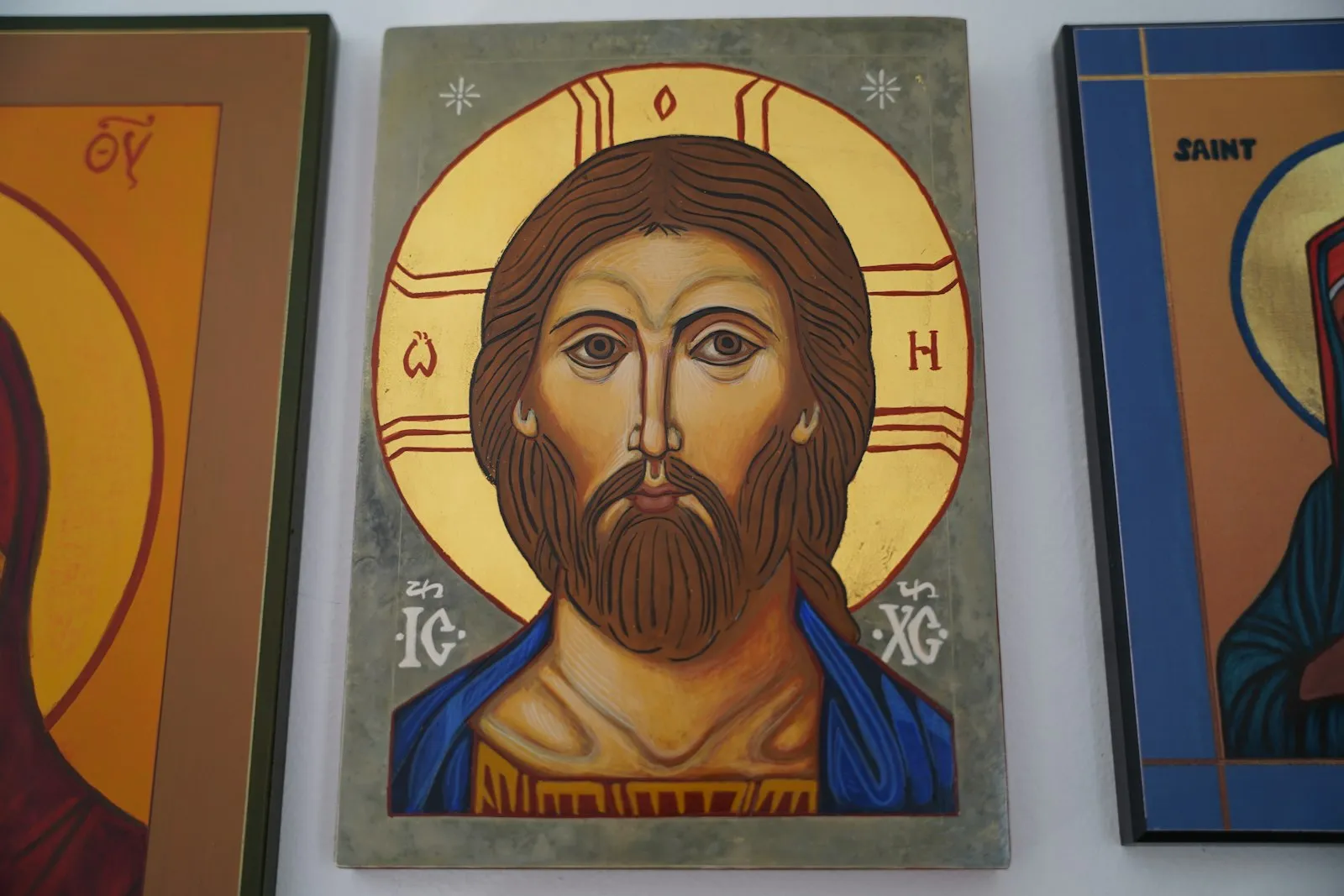

Crombie wrote two icons in the workshop, Jesus Christ Pantocrator and the Virgin of Vladimir; icons are “written,” not drawn or painted, because the imagery and symbolism of iconography constitute a language that can be read.

In addition to learning how to write an icon, Crombie learned more about the theology behind the ancient tradition.

“Many people will tell you standing before an icon to pray is a door to the divine,” Crombie said. “I think that’s a good summary. Actually, I think it’s a door to the divine that allows us to step through to that divine person and image. When you pray before an icon, it’s like going to a meeting. When you get to a meeting, you prepare; there are expectations about what you will accomplish in that meeting. Going in front of an icon is the same thing. You go with the expectation of a meeting with the holy person.”

Crombie returned to Michigan and put her newfound skills to good use. She was on the steering committee for the Archdiocese of Detroit’s Women’s Conference in the early 2000s, and when the event moved to the Macomb Community College Fieldhouse, the conference needed a large cross to fit the space for Mass.

“We needed this huge, huge cross, but there wasn’t one available,” Crombie said. “I said to the steering committee, ‘I can do it.’ I don’t know if I want it, I don’t know if God wants it, but if you want it, I can do an icon. What emerged was a 14-foot cross my friend made, and I did this 6-foot-5 Jesus icon that we mounted on the cross.

“The work was magnificent, and I can say that because in iconography, God is the artist,” Crombie added. “I just mix the paint and hold the brush. An iconographer doesn’t sign the work because it is God’s; it’s not yours.”

The 6-foot-5 icon now resides in the offices of Father John Riccardo’s ACTS XXIX ministry.

Being able to draw such an icon after completing only two others at a workshop shows how God is always in control in the iconography process, from discerning whether an icon should be created to planning out how it will look, Crombie said.

“God is in control, always,” Crombie said. “It’s always his will. I learned that God works through you if you open yourself to him. I know that for a fact. I look at certain icons in particular and stand back and go, ‘I know I was part of that, but I didn’t do that.’ I don’t know how to describe it otherwise; it is knowing that God did that, and no one could tell me differently.”

Iconographers see themselves as instruments of God’s will, Crombie said. In order to complete an icon — or even start an icon — everything must be done in prayer, Crombie said.

“The icon begins in prayer, stays in prayer, and ends in prayer,” Crombie said. “I’m not one of the old monks in the monastery who does this 24/7, but it is a product of prayer and whether or not God wants an icon. So when someone commissions me, I tell them I’ll pray. I’ll pray for a couple of weeks to confirm whether or not God wants this. And most of the time he does; there have only been a couple of times where he said no or maybe, but not right now. And the people have been understanding and agreeable with it. So we are praying for God’s will.”

Icons have more of a tradition in the Eastern Church, with the faithful able to recognize saints and holy people through the usage of symbols, colors, and placements of different elements of the icon on the canvas.

Icons are less like stained-glass windows, which depict saints and various moments in salvation history, and more like testaments to the constant presence that saints have in the Church, Crombie said.

“In the Eastern Church, to go before an icon means to be in front of that individual, one-on-one. They use the image liturgically, somewhat differently than the Roman Catholic Church,” Crombie said. “When you go to an Orthodox Church, you will see icons everywhere; you see them in their liturgy. It’s how they show the divine. We can use a camera show how a person looks, an artist can draw how they perceive a person, but when we see a person through God’s eyes, that’s an icon. So they might have longer fingers, elongated faces, depending on the icon and where it’s from and the person it depicts.”

Two of Crombie’s favorite commissioned icons are at the Divine Mercy Center in Clinton Township, Michigan: Our Lady of Guadalupe and the Image of Divine Mercy.

Crombie’s relationship with the Divine Mercy Center, the Servants of Jesus the Divine Mercy, and its foundress Catherine Lanni began during a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

The two women didn’t know each other before the trip but connected after hearing a talk from Rwandan holocaust survivor Immaculée Ilibagiza. The group was standing at the foot of Mount Tabor in Israel, where Ilibagiza said Our Lady of Kibeho is her favorite devotion.

“She was talking about this devotion, and I was walking away thinking, ‘Maybe Our Lady is calling me to write an icon of Our Lady of Kibeho that’s life-sized,’” Crombie said. “She and I were praying that, and we prayed for a year about this. It was getting frustrating because I wanted to hear the Lord say yes, and we were hearing nothing.”

She kept praying on it when in April of that year, she received an invitation to go to a conference at St. Stanislaus Kostka Parish in Chicago, the sanctuary for the Divine Mercy in the Archdiocese of Chicago, a conference Lanni also attended.

“On the way back from the conference, Catherine called me to be on the board of the Divine Mercy [Center], and she wanted me to write an icon of Jesus the Divine Mercy,” Crombie said. “And God’s timing was interesting. I really thought I was going to write an icon of Our Lady of Kibeho, but it is just like Our Lady to say, ‘Not me; do my son, the Divine Mercy.’ And the Mother is right. That led to the Divine Mercy icon that is now at the Shrine of Jesus the Divine Mercy.”

A key feature of iconography is learning the language of the art, how each and every element of an icon is deliberate in telling the story of the person depicted.

“Everything in an icon means something; it’s not just happenstance,” Crombie said. “So the colors, the movement of the hand, the glace, it all means something, and the iconographer knows that. Much how like stained-glass is a story, iconography is a story. In the Eastern Church, they know how to read an icon. They grow up with it.”

For example, there are certain elements common to each icon of a person, especially Jesus or Mary.

“[When] you depict Jesus in icon, either by himself or in a group, he is the only one with a cruciform halo,” Crombie explained. “The other thing you see with Jesus are the letters next to him, ICXC, the first and last letters of ‘Jesus Christ’ in Greek. With Our Lady, she is the Theotokos, the God-bearer, and you’ll see the symbols there. With Mary, generally, you will see her with three stars on her forehead and shoulders, depicting her virginity before, during, and after the birth of Christ.”

Crombie said learning more about the history and theology behind icons has been a great joy, but it would not be possible without God’s divine hand guiding her work.

“It’s clear to me that it is God who writes them; I’m just the willing vessel that he uses,” Crombie said. “When I get stuck on something, I pray for his direction. He is it. Without the Lord, iconography is just another painting. I can look back and think, ‘This is awesome,’ and not feel like I’m being conceited at all, because it is all him.”

Crombie’s work can be seen at the Shrine of Jesus the Divine Mercy in Clinton Township and in the Eucharistic chapel at the Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrament in Detroit. Her home is decorated with replications of icons she has completed for private commissions.

Iconography isn’t a hobby for Crombie but rather something she weaves into the rest of her life, including her pro-life witness, connecting it all to depicting and defending the image and likeness of God.

“The overlap between pro-life work and iconography is about the image of God,” Crombie said. “We are all created in the image of God.”

Crombie is hesitant to identify her favorite icon, but she does have a soft spot for Jesus the Divine Mercy. Still, Crombie said the quality of an icon is less in the artist’s skill but the prayer that went into drawing the icon and the faith it will inspire.

“It has nothing to do with the quality of the work,” Crombie said. “It has to do with the Divine Image and the prayer. You can have the most simplistic icon and still have it be of great value in the eyes of prayer. It is all about the prayer and not the quality of the work.”

This article was originally published by Detroit Catholic on April 3, 2024, and is reprinted here with permission.