New Orleans Auxiliary Bishop Cheri dies at 71 after lengthy illness

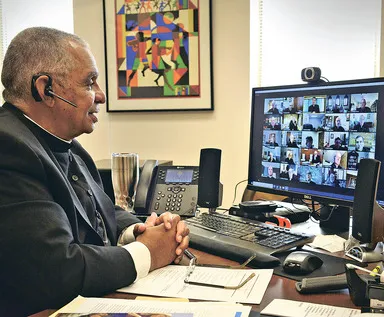

Bishop Fernand (Ferd) Joseph Cheri III, OFM, at his ordination as auxiliary bishop of New Orleans in 2015. / Credit: Clarion Herald

Bishop Fernand (Ferd) Joseph Cheri III, OFM, at his ordination as auxiliary bishop of New Orleans in 2015. / Credit: Clarion Herald New Orleans, La., Mar 22, 2023 / 16:00 pm (CNA).

Bishop Fernand (Ferd) Joseph Cheri III, OFM, a New Orleans native who had served since 2015 as auxiliary bishop of New Orleans, died March 21 at Chateau de Notre Dame in New Orleans following a lengthy illness.

Cheri, 71, served most recently as administrator of St. Peter Claver Parish in New Orleans until kidney and heart problems forced him to step away from active ministry. He was born with one kidney and had been on dialysis three days a week for several months.

“He has been called home to the Lord,” Archbishop Gregory Aymond said in a message to priests, religious, and laity of the archdiocese. “We mourn his death and thank God for his life and ministry.”

The archbishop said Cheri started his vocational journey in the Archdiocese of New Orleans “as a seminarian, as a priest, and as a pastor” and had directed a “very dedicated ministry.”

“And then, he heard God’s call to join the Franciscans and was a valued member of the Franciscan community,” Aymond said. “We were delighted to receive him back into the Archdiocese of New Orleans as auxiliary bishop in 2015, and I have enjoyed working with him in sharing episcopal ministry and shepherding God’s people.”

Lengthy medical setbacks

Cheri was hospitalized after attending the national Lyke Conference for Black Catholics last June, and he began dialysis several months later and was dealing with a serious heart condition.

“We saw him not only as a vocal advocate for African-American Catholics and advocating for our needs but also as a shepherd to the world,” said Dr. Ansel Augustine, director of the archdiocesan Office of Black Catholic Ministries. “When you think of bishops being shepherds, you see someone who cares about people, one on one. When you talked to him, you felt like you were the only person in the world that mattered even though he might have had 8 million other things going on. But Bishop Cheri’s charism — and maybe it’s the Franciscan thing of hospitality — was something you felt with him. I think that’s why so many people loved him.”

Cheri, who was ordained to the episcopacy on March 23, 2015, at St. Louis Cathedral, was one of seven active African-American bishops in the U.S.

In 2020, after the murder of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis, Cheri led a peaceful march of 250 from the archdiocesan chancery building to Notre Dame Seminary. The prayer service was called “Requiem for the Black Children of God.”

“Enough is enough,” he said from the steps of the seminary, where he did his theological studies. “This scene drains our spirits and clouds the union of the human family.

“As toxic as the crossroads of life are these days, will we have the courage and wisdom to stay vigilant amidst … the gross violence and abuse by law enforcement? This is not a time for the faint of heart but for the courageous.”

In a 2018 address honoring New Orleans’ tricentennial, Cheri traced the history of the Black Catholic Church in New Orleans and praised the Sisters of the Holy Family, founded in 1842 by Venerable Henriette Delille, a free woman of color; the Knights and Ladies of St. Peter Claver; the Office of Black Catholic Ministries; and the Institute of Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana, founded in 1980 to explore Scripture and Church teachings from both “a righteous Black consciousness and an authentic Catholic tradition.”

“These individuals and moments challenged the Catholic community of the Archdiocese of New Orleans to not only change the narrative of the Church but [also] to affirm that we share common journeys together,” Cheri said. “We were called to rise above the Code Noir and Jim Crow laws of our times that supported the politics of fear and anger and the foundation of racism in the South.”

Music tied to his faith life

A lifelong singer, he loved to break into song during a homily or whenever the mood struck. When he was just 3 years old, his mother, Gladys, recalled little Ferd, the first boy among her seven children, belting out a tune in their house on St. Anthony Street in New Orleans.

In a 2015 interview before his ordination, Cheri spoke about how he reveled in the gift of music and his vocation.

“The experience of becoming a bishop — and how people are reacting to it — I feel like I sang a solo that became the community’s prayer,” he told the Clarion Herald.

Cheri was named the 11th auxiliary bishop of New Orleans on Jan. 12, 2015. Until he received the phone call from the papal nuncio, the self-effacing Franciscan priest was directing campus ministry at Quincy University, a 1,300-student school run by the Franciscans in rural Illinois, about 135 miles northwest of St. Louis.

Cheri’s life story was one of amazing grace.

His father, Fernand Joseph Cheri Jr., was an Army veteran whose full-time job was delivering mail. He worked extra jobs to keep the children fed and in Catholic school uniforms. After finishing his regular mail route at 3 p.m., Cheri would drive to St. Mary’s Academy to do evening maintenance work. Later, he even helped build classroom buildings at the school.

Gladys Cheri, who squeezed every nickel out of her husband’s salary, somehow made it all work. Gladys also worked for many years cooking for the Sisters of the Holy Family who staffed St. Mary’s Academy.

“It was quite interesting,” Bishop Cheri said. “My dad would always say, ‘Y’all are breaking me!’ That was his favorite mantra. Of course, that never stopped us from saying we needed money. Somehow, we made it. When I think about living in a house with one bathroom for nine people, that’s amazing.”

At Epiphany Church, the Cheri family arrived like ducks, walking single file and taking up an entire pew. Young Ferd was too impatient and undisciplined to learn the piano from choir director James Freeman, but the young singer always could carry a tune.

“He tried to get me to sing solos at church,” Cheri recalled. “I got up one day and I was so nervous and shaking that my voice quivered so badly. No one came to my rescue. I had to bear that cross alone.”

In the 1960s, when the archdiocese was making efforts to desegregate its churches and the Cheris had moved into St. Leo the Great Parish, Archbishop Joseph Rummel, working through the Epiphany pastor, asked them to attend Mass at the previously all-white St. Leo the Great.

Even though they were leaving behind all their church friends at Epiphany, Bishop Cheri’s parents respected the archbishop’s wishes.

“They did that to integrate the church,” Cheri said. “We were just going to do it. I don’t think there was any conversation about it.”

That experience, as mysterious as it was, was an important signpost of what it meant to grow up both black and Catholic in New Orleans. As a member of Epiphany — which was staffed by Josephite priests — Cheri grew up in a protective cocoon where there was a sense of “really strong community.”

“We were protected from a lot of the racism in the country and even in the city,” he said.

Even after his family began attending St. Leo the Great Church, Ferd continued attending Epiphany School, and he began thinking about the priesthood.

St. John Prep

He chose to attend St. John Prep, then a school for young men considering the priesthood. Cheri played fullback on the Chargers’ football team and sang in the glee club. While there, he met two other religious women — Marianite Sister Judy Gomila and Sister of the Holy Family Marie Bernadette — who worked in the Ninth Ward with the needy in St. Philip the Apostle Parish, which encompassed the Desire Housing Development.

“They were always showing us what we needed to do,” Cheri said. “They encouraged us by saying, ‘You can do this. You can do that.’ Sister Judy and Sister Bernadette were a great team.”

“Some people called us salt and pepper,” said Sister Judy, who is white. “I will remember his wonderful voice and his gift of music. He could sing even when he was sad.”

When Cheri went on to St. Joseph Seminary College in Covington, there were about 15 Black seminarians studying for dioceses across Louisiana.

There were difficult challenges. Sometimes it was an insensitive, racially charged remark by a professor that left him wondering if he truly would be able to persevere in his vocation. But every time something traumatic occurred, Cheri said, someone came into his life to help reassure him and save his vocation.

Many of those “father figures” were members of the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus, whom he had met during summer conferences. They became sounding boards whenever things got rough. He mentioned Father Thomas Glasgow, a New Orleans priest.

“There were a number of Black priests in the clergy caucus who were supportive of me,” Cheri said. “To hear some of those guys tell their stories about how they survived and stayed in the seminary, I felt like what I was going through, as difficult as it was, was nothing compared to what they went through.”

By the time he got to Notre Dame Seminary to begin his theology studies, Cheri felt compelled to learn everything he could about ministering to all people. He took a mission trip to Jamaica, and his role was to help run a catechetical program at an orphanage.

He was selected in the summer of 1976 to serve as a chaplain at California State Prison in Vacaville, a medical prison with 2,300 inmates. On his first day, he went for lunch and turned around with his tray only to see only one spot left at a table for six — and the other five men sitting at the table were inmates.

“I was scared to death,” Cheri said. “Of course, I was in my clerics, and to all of these guys, I was a Black Catholic priest, and they had never seen one before, nor did they care. I was the smallest person there. I felt like I was sitting with a football team. It was a moment where I had to be myself, but I also had to show a sense of self-assurance, otherwise it would have been damaging. In those 10 weeks, my ministry at Vacaville gave me the courage to go on to be a priest.”

He was ordained to the diaconate in January 1978 at Epiphany Church and then was ordained to the priesthood by Archbishop Philip Hannan on May 20, 1978, at St. Louis Cathedral.

He was assigned for a year to Our Lady of Lourdes in New Orleans, whose pastor was Bishop Harold Perry, and then went in 1979 to St. Joseph the Worker Parish in Marrero, working under Father Doug Doussan.

Just as he had at Our Lady of Lourdes, Father Cheri developed a strong music ministry, building a 70-member youth choir within three months. Even then, he had to tread carefully because there was a delicate balance between white and Black parishioners, and the youth choir was made up of mostly Black teens.

“We had so many people at church, we had to start another Mass,” Cheri said. “I made sure the leadership of the parish understood what was going to happen and what differences it would make culturally for the Mass.”

Parishioners reacted positively to the new music program.

“One woman got up and said, ‘I have all my young children in the choir and I used to battle with them about going to church,’” Cheri said. “‘Now, they’re battling with me to get me to church.’ That whole experience taught me that we really need to help people see the value of our differences. Sometimes we just don’t see it. We go with how we think things should be, but our view is not the only view.”

After serving from 1985-91 as pastor of St. Francis de Sales Parish in New Orleans, Cheri said he began to feel a tug to consider joining a religious community.

“I was toying with the idea because I was living alone and I had some nights when I just wished I could talk to somebody about stuff,” Cheri said. “You can call a friend, but it’s different when you’re eating with somebody and can share your day and what’s going on in your life.”

He began by calling the superiors of several different religious communities with whom he had experience working in New Orleans — the Franciscans, Josephites, Vincentians, Dominicans, and Holy Cross Fathers. Each superior came to New Orleans to meet with him.

“Basically, I chose the Friars because of St. Francis and his idea of service to the poor, the marginalized, the variety of possibilities of working with the homeless people or in prison ministry,” Cheri said. “I felt I wanted to do something other than just parish ministry. The Friars offered that possibility to me. I also knew of a lot of Black Friars who were working around the country. I thought this might be a good fit.”

Cheri spent one year in the Franciscans’ pre-novitiate, which gave him a chance to see what living in community was all about while doing prison ministry in Joliet, Illinois.

He then went for two years of study in the novitiate in Franklin, Indiana, in order to learn more about the ministries and inner workings of the Franciscans’ Province of the Sacred Heart.

He taught and was a campus minister at Hales Franciscan High School in Chicago from 1993-96 and then served from 1996-2002 as pastor of St. Vincent de Paul Church in Nashville, Tennessee, that diocese’s only Black Catholic parish.

From 2002-2008, he helped in a special project of the Friars in East St. Louis, Illinois, living at St. Benedict the Black Friary and working as a guidance counselor and choir director at Althoff Catholic High School in Belleville, Illinois. While at Althoff, Cheri also tried to convince parents to do anything they could to send their children to a Catholic high school.

“It was the best secret in the Diocese of Belleville,” Cheri said. “I wanted to get some of the kids from East St. Louis to go there because the public high school was horrible. The dropout rate in the public high school was terrible. Sixty-seven percent of the freshman class never made it to graduation. You needed an alternative place.”

After spending a year as associate director of campus ministry at Xavier University back home in New Orleans, Cheri served for three and a half years as campus minister at Quincy University.

And then he returned to the city of his birth, where his parents scrimped and saved, worked and worshiped, to make something of their lives. He can hear the music of his birth.

Shall we gather at the river?

“I’ve never left New Orleans,” he said. “It’s always been a part of me.”

The article was originally published on the Clarion Herald website and is republished with permission on CNA.