5 things to know about popular piety and Pope Francis’ trip to Corsica

The sun rises over the island of Corsica, France. / Credit: Andrew Mayovskyy/Shutterstock

The sun rises over the island of Corsica, France. / Credit: Andrew Mayovskyy/Shutterstock Rome Newsroom, Dec 13, 2024 / 06:00 am (CNA).

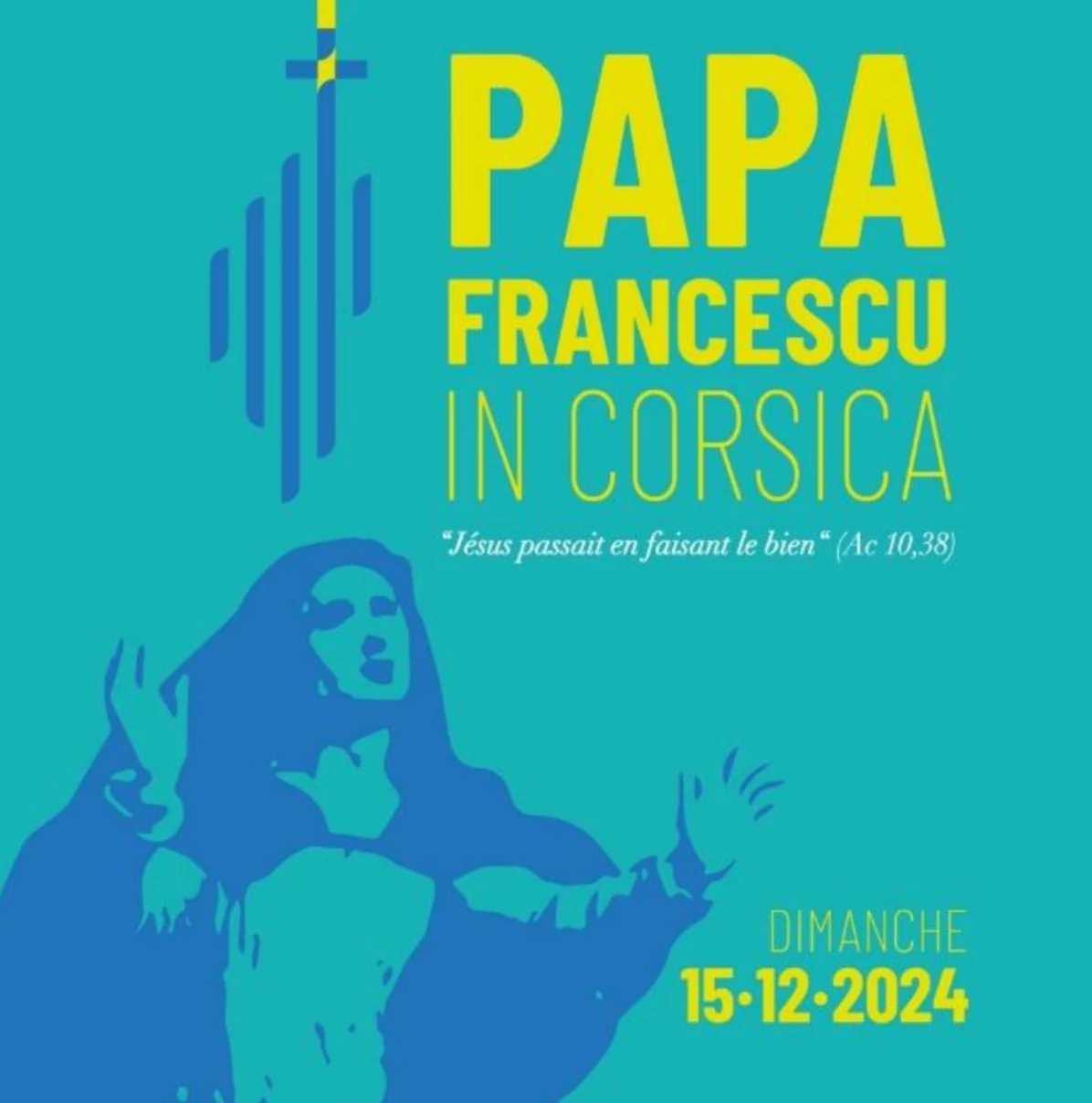

On Dec. 15, Pope Francis will travel to Ajaccio, the capital of the French island of Corsica, for a less than nine-hour visit.

Part of the pope’s itinerary for the short trip is to speak at the closing of a conference on popular piety in the Mediterranean region.

Here are some answers to questions about the pope’s very brief international trip:

Where is Corsica?

Corsica is an island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is situated west of the mainland of Italy and north of the Italian island of Sardinia, the nearest land mass.

The island was annexed by France in 1769, the year after Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte was born in the region’s capital city of Ajaccio.

French is the most widely spoken language on the island, together with Corsican. Some areas also speak a regional Italo-Dalmatian language.

Corsica’s population is estimated to be 355,528, according to data from January.

The island region has a strong autonomy movement steeped in national identity and pride, which aims to achieve the further political autonomy of Corsica from France.

What will Pope Francis do there?

Pope Francis’ first appointment in Corsica after landing around 9 a.m. will be at Ajaccio’s conference center, where he will deliver the closing speech following a daylong conference on Dec. 14 about popular piety in the Mediterranean region.

The pope will then address local clergy and religious at the Cathedral of Our Lady of Assumption, where he will also lead the Angelus, a traditional Marian prayer.

After lunch and some time to rest, Francis will preside at Mass with local Catholics at Place d’Austerlitz, a park memorializing the birthplace of Napoleon Bonaparte, before his last stop — a private meeting with France’s President Emmanuel Macron.

Pope Francis is expected to arrive back in Rome around 7 p.m.

“It will be important to hear Pope Francis’ words at the conclusion of the conference [on popular piety in the Mediterranean],” an Italian archbishop who will present a paper at the conference told CNA’s Italian-language news partner, ACI Stampa. “He is very sensitive to the theme of popular piety.”

The pope’s remarks “will be an invitation to all, bishops, priests, and laity, to value this journey of faith, listening carefully when it is lived in communities. It will also be a commitment to further formation and evangelization of those areas that need … to be purified and clarified,” Archbishop Roberto Carboni of the Italian Dioceses of Oristano and Ales-Terralba said.

What is popular piety?

Also sometimes called “popular religiosity,” acts of popular piety are expressions of the faith apart from the liturgy.

In the “Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy: Principles and Guidelines,” published by the then-Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments in 2001, the Vatican described popular piety as “diverse cultic expressions of a private or community nature which, in the context of the Christian faith, are inspired predominantly not by the sacred liturgy but by forms deriving from a particular nation or people or from their culture.”

Some examples of popular piety are the rosary, religious processions for holy days and saints’ days, and Eucharistic processions.

St. John Paul II, in a 1982 speech to the bishops of France, said popular piety is simply “faith deeply rooted in a particular culture, immersed in the very fiber of hearts and ideas. Above all, it is generally shared by people at large who are then a people of God.”

Pope Benedict XVI, in an address in Aparecida, Brazil, in 2007, called popular piety “a precious treasure of the Catholic Church in Latin America” that “must be protected, promoted, and, when necessary, purified.”

Popular piety in the Mediterranean is often closely linked to Catholic fraternities and confraternities — associations of laypeople dedicated to charitable work and religious devotions.

The island region of Corsica has a strong tradition of confraternities, Father Juan Miguel Ferrer Grenesche, an expert in popular piety, told CNA’s Spanish-language news partner, ACI Prensa.

The confraternities in Corsica include influences from Italy and the south of France, brought there by “the Dominicans and Franciscans who preached and cared for these areas of the Mediterranean,” the Spanish priest said.

Over the years, “people followed it as something very much their own and very particular, and the singing, which is very important in Corsica, has also been preserved,” Ferrer explained. The Corsican singing is characterized by being “very peculiar, nasal, and attention-grabbing.”

What has Pope Francis said about popular piety?

Pope Francis has spoken often in support of popular piety among religious people — calling it a “jewel” — and the power of pious devotions to evangelize.

In Evangelii Gaudium, Francis’ 2013 apostolic exhortation, there is a chapter on “the evangelizing power of popular piety” in which the pope said “popular piety enables us to see how the faith, once received, becomes embodied in a culture and is constantly passed on.”

“Expressions of popular piety have much to teach us; for those who are capable of reading them, they are a locus theologicus which demands our attention, especially at a time when we are looking to the new evangelization,” the pope wrote.

In his recent encyclical on the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Dilexit Nos, Francis asked people to take seriously the “fervent devotion” of those who seek to console Christ through acts of popular piety.

“I also encourage everyone to consider whether there might be greater reasonableness, truth, and wisdom in certain demonstrations of love that seek to console the Lord than in the cold, distant, calculated and nominal acts of love that are at times practiced by those who claim to possess a more reflective, sophisticated, and mature faith,” he added.

Pope Francis has also recently noted how to outsiders, the demonstrations of those who participate in religious processions (one common form of popular piety) may seem “crazy” — “But they are mad with love for God.”

In a message to a conference on religious fraternities and popular piety in Seville, Spain, Dec. 4–8, the pope said: “Above all, it is the beauty of Christ that summons us, calls us to be brothers and sisters, and urges us to take Christ out into the streets, to bring him to the people, so that everyone can contemplate his beauty.”

Popular piety in the Mediterranean today

Two bishops and a priest scheduled to speak at the Dec. 14 conference in Ajaccio explained that popular piety is an important link to transcendence and faith in an increasingly secular Mediterranean region.

Bishop Calogero Peri of Caltagirone, Sicily, told CNA that religious celebrations surrounding Holy Week, Marian feast days such as the Assumption and the Immaculate Conception, and local patronal feast days are still very important in the hearts and lives of many Sicilians.

Of course, he noted, “some people have become more spectators than participants” in the celebrations, which commonly include both penitential and jubilant processions.

Archbishop Carboni of the Italian dioceses of Oristano and Ales-Terralba also affirmed the popularity of religious processions in Italy and told ACI Stampa that popular piety is “a prayer with the heart made action.”

Carboni and Peri both praised the ability of these people’s movements with their sounds, sights, and smells to affect people beyond a rational level, touching their hearts, minds, and souls.

They are a great legacy worth preserving and a “very valid way of [practicing the] faith,” Peri added.

Spanish Father Ferrer said popular piety, for many people, is “the last lifeline to connect with transcendence and to avoid breaking completely with the Christian religious tradition.”

In evangelization, popular piety also makes it possible to reach those who do not know the depth and richness of formal liturgy and, through “a cultural adaptation,” is able to “preserve the link between the thirst for God of the human heart and the sources of revelation: the word of God, the life of Christ, the sacraments, the Church itself,” he said.

“On the contrary,” he added, “where all manifestations of popular religiosity or popular piety have been eliminated, we could say that people’s souls have dried up.”