The healing of a Royal Navy sailor at Lourdes

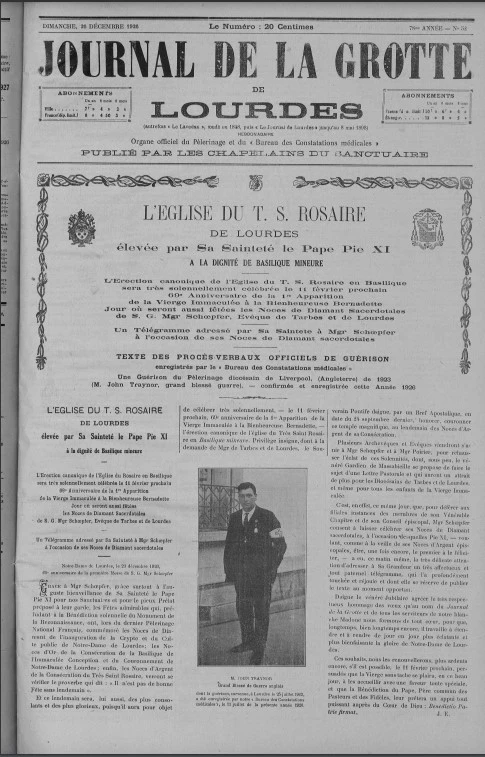

Jack Traynor (next to child on first row) as a pilgrim to Lourdes in 1925, two years after his healing. / Credit: Catholic Bishops' Conference of England and Wales

Jack Traynor (next to child on first row) as a pilgrim to Lourdes in 1925, two years after his healing. / Credit: Catholic Bishops' Conference of England and Wales ACI Prensa Staff, Dec 14, 2024 / 08:00 am (CNA).

In 1944, Father Patrick O’Connor, an Irish priest and member of the Missionary Society of St. Columban, published “I Knew a Miracle: The Story of John Traynor, Miraculously Healed at Lourdes.”

In the book he recounts how, during a 10-hour train ride to Lourdes on Friday, Sept. 10, 1937, Royal Navy seaman Jack Traynor told him firsthand how he was healed in 1923 at the Lourdes Shrine from the crippling wounds he had suffered from his participation in World War I.

Over a century later, on Dec. 8 of this year, the archbishop of Liverpool in the United Kingdom, Malcolm McMahon, announced that Traynor’s healing has been recognized as the 71st miracle attributed to the intercession of Our Lady of Lourdes.

O’Connor described Traynor as a “heavy-set man, 5’5”, with a strong, ruddy face” who, according to his biography, “should have been, if he were alive, paralyzed, epileptic, covered in sores, shrunken, with a wrinkled and useless right arm and a gaping hole in his skull.”

Traynor was, in the missionary’s view, a man “with his manly faith and piety,” unassuming, “but obviously a fearless, militant Catholic.” Despite having received only a primary education, he had “a clear mind enriched by faith and preserved by great honesty of life.”

This enabled him to tell “with simplicity, sobriety, exactness” how he was healed at the place where the Immaculate Conception appeared to St. Bernadette Soubirous in 1858.

O’Connor wrote down the account and sent it to Traynor, who revised it and added new details. He read the official report of the doctors who examined him and searched the newspaper archives of the time to corroborate the account.

How Traynor came to be considered incurable

Traynor was born in Liverpool, according to some sources, in 1883. His mother was an Irish Catholic who died when Traynor was still young. “But his faith, his devotion to the Mass and holy Communion — he went daily when very few others did — and his trust in the Virgin remained with him as a fruitful memory and example,” O’Connor recalled.

Mobilized at the outbreak of World War I, he was hit by shrapnel, which left him unconscious for five weeks. Sent in 1915 to the expeditionary force to Egypt and the Dardanelles Strait, between Turkey and Greece, he took part in the landing at Gallipoli.

During a bayonet charge on May 8, he was hit with 14 machine gun bullets in the head, chest, and arm. Sent to Alexandria, Egypt, he was operated on three times in the following months to try to stitch together the nerves in his right arm. They offered him amputation, but he refused. The epileptic seizures began, and there was a fourth operation, also unsuccessful, in 1916.

He was discharged with a 100% pension “for permanent and total disability,” the missionary priest related, and in 1920 he underwent surgery on his skull to try to cure the epilepsy. From that operation he was left with an open hole “about two centimeters wide” that was covered with a silver plate.

By then he was suffering three seizures a day and his legs were partially paralyzed. Back in Liverpool he was given a wheelchair and had to be helped out of bed.

Eight years had passed since the landing at Gallipoli. Traynor was treated by 10 doctors who could only attest “that he was completely and incurably incapacitated.”

Unable to walk, with epileptic seizures, a useless arm, three open wounds, “he was truly a human wreck. Someone arranged for him to be admitted to the Mossley Hill Hospital for Incurables on July 24, 1923. But by that date Jack Traynor was already in Lourdes,” O’Connor recounted.

Traynor tells about his pilgrimage to Lourdes

According to the first-person account originally written by O’Connor and corrected and adapted by Traynor, the veteran sailor had always felt great devotion to Mary that he got from his mother.

“I felt that if the shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes were in England, I would go there often. But it seemed to me a distant place that I could never reach,” Traynor said.

When he heard that a pilgrimage was being organized to the shrine, he decided to do everything he could to go. He used money set aside “for some special emergency” and they even sold belongings. “My wife even pawned her own jewelry.”

When they learned of his determination, many tried to dissuade him: “You’ll die on the way, you’ll be a problem and a pain for everyone,” a priest told him.

“Everyone, except my wife and one or two relatives, told me I was crazy,” he recalled.

The experience of the trip was “very hard,” confessed Traynor, who felt very ill on the way. So much so that they tried to get him off three times to take him to a hospital in France, but at the place where they stopped there was no hospital.

On arrival at Lourdes, there was ‘no hope’ for Traynor

On Sunday, July 22, 1923, they arrived at the Lourdes Shrine in the foothills of the French Pyrenees. There he was cared for by two Protestant sisters who knew him from Liverpool and who happened to be there providentially.

The pilgrimage of more than 1,200 people was led by the archbishop of Liverpool, Frederick William Keating.

On arrival, Traynor felt “desperately ill,” to the point that “a woman took it upon herself to write to my wife telling her that there was no hope for me and that I would be buried at Lourdes.”

Despite this, “I managed to get lowered into the baths nine times in the water from the spring in the grotto and they took me to the different devotions that the sick could join in.”

On the second day, he suffered a strong epileptic seizure. The volunteers refused to put him in the pools in this state, but his insistence could not be overcome. “Since then I have not had another epileptic seizure,” he recalled.

Paralyzed legs healed

On Tuesday, July 24, Traynor was examined for the first time by doctors at the shrine, who testified to what had happened during the trip to Lourdes and detailed his ailments.

On Wednesday, July 25, “he seemed to be as bad as ever” and, thinking about the return trip planned for Friday, July 27, he bought some religious souvenirs for his wife and children with the last shillings he had left.

He returned to the baths. “When I was in the bath, my paralyzed legs shook violently,” he related, causing alarm among the volunteers who attended to the pilgrims at the shrine, believing it was another epileptic seizure. “I struggled to stand up, feeling that I could do so easily,” he explained.

Arm healed as Blessed Sacrament passes by

He was again placed in his wheelchair and taken to the procession of the Blessed Sacrament. The archbishop of Reims, Cardinal Louis Henri Joseph Luçon, carried the monstrance.

“He blessed the two who were in front of me, came up to me, made the sign of the cross with the monstrance, and moved on to the next one. He just passed when I realized that a great change had taken place in me. My right arm, which had been dead since 1915, shook violently. I tore off its bandages and crossed myself, for the first time in years,” Traynor himself testified.

“As far as I can remember, I felt no sudden pain and certainly I did not have a vision. I simply realized that something momentous had happened,” Traynor recounted.

Back at the asylum, the former hospital that today houses the offices of the Hospitality of Our Lady of Lourdes, he proved that he could walk seven steps. The doctors examined him again and concluded in their report that “he had recovered the voluntary use of his legs” and that “the patient can walk with difficulty.”

Traynor makes it to the grotto

That night, he could hardly sleep. As there was already a certain commotion around him, several volunteers stood guard at his door. Early in the morning, it seemed that he would fall asleep again, but “with a last breath, I opened my eyes and jumped out of bed. First I knelt on the floor to finish the rosary I had been saying, then I ran to the door.”

Making his way, he arrived barefoot and in his pajamas at the grotto of Massabielle, where the volunteers followed him: “When they reached the grotto, I was on my knees, still in my nightclothes, praying to the Virgin and thanking her. I only knew that I had to thank her and that the grotto was the right place to do so.”

He prayed for 20 minutes. When he got up, a crowd surrounded him, and they made way to let him return to the asylum.

A sacrifice made for the Virgin in gratitude

“At the end of the Rosary Square stands the statue of Our Lady Crowned. My mother had always taught me that when you ask the Virgin for a favor or want to show her some special veneration, you have to make a sacrifice. I had no money to offer, having spent my last shillings on rosaries and medals for my wife and children, but kneeling there before the Virgin, I made the only sacrifice I could think of. I decided to give up smoking,” Traynor explained with tremendous simplicity.

“During all this time, although I knew I had received a great favor from Our Lady, I didn’t clearly remember all the illness I previously had,” he noted in his account.

As he finished getting himself ready, a priest, Father Gray, who knew nothing of his cure, asked for someone to serve Mass for him, which Traynor did: “I didn’t think it strange that I could do it, after eight years of not being able to get up or walk,” he said.

Traynor received word that the priest who had strongly opposed his joining the pilgrimage wanted to see him at his hotel, located in the town of Lourdes, outside the shrine. He asked him if he was well. “I told him I was well, thank you, and that I hoped he was too. He burst into tears.”

Early on Friday, July 27, the doctors examined Traynor again. They found that he was able to walk perfectly, that his right arm and legs had fully recovered. The opening in his skull resulting from the operation had been considerably reduced, and he had not suffered any further epileptic seizures. His sores had also healed by the time he returned from the grotto, when he had removed his bandages the previous day.

Weeping ‘like two children’ with Archbishop Keating

At nine o’clock in the morning the train back to Liverpool was ready to leave the Lourdes station, situated in the upper part of the town. He had been given a seat in first class, which, despite his protests, he had to accept.

Halfway through the journey, Keating came to see him in his passenger car. “I knelt down for his blessing. He raised me up saying, ‘Jack, I think I should have your blessing.’ I didn’t understand why he was saying that. Then he raised me up and we both sat on the bed. Looking at me, he said, ‘Jack, do you realize how ill you have been and that you have been miraculously cured by the Blessed Virgin?’”

“Then,” Traynor continued, “it all came back to me, the memory of my years of illness and the sufferings on the trip to Lourdes and how ill I had been at Lourdes. I began to cry, and so did the archbishop, and we both sat there crying like two children. After talking to him for a while, I calmed down. I now fully understood what had happened.”

A telegram to his wife: ‘I am better’

Since news of the events had already reached Liverpool, Traynor was advised to write a telegram to his wife. “I didn’t want to make a fuss with a telegram, so I sent her this message: ‘I am better — Jack,’” he explained.

This message and the letter announcing that her husband was going to die in Lourdes were all the information his wife had, as she had not seen the newspapers. She assumed that he had recovered from his serious condition but that he was still in his “ruinous” state.

The reception in Liverpool was the culmination. The archbishop had to address the crowd to disperse at the mere sight of Traynor getting off the train. “But when I appeared on the platform, there was a stampede” and the police had to intervene. “We returned home and I cannot describe the joy of my wife and children,” he said in his account.

A daughter named Bernadette

Taynor concluded his account by explaining that in the following years he worked transporting coal, lifting 200-pound sacks without difficulty. Thanks to providence, he was able to provide well for his family.

Three of his children were born after his cure in 1923. A girl was named Bernadette, in honor of the visionary of Lourdes.

He also related the conversion of the two Protestant sisters who cared for him, along with his family and the Anglican pastor of his community.

From then on, Jack volunteered to go to Lourdes on a regular basis until he died in 1943, on the eve of the solemnity of the Immaculate Conception.

Paradoxically, and despite the factual evidence of his recovery, the Ministry of War Pensions never revoked the disability pension that was granted to him for life.

This story was first published by ACI Prensa, CNA’s Spanish-language news partner. It has been translated and adapted by CNA.